In 1898 young Winston Churchill, after a couple other writing gigs (Daily Graphic, Telegraph) went off to war with a commission to write for The Morning Post. He produced thirteen articles between September 23 and October 8, 1898 for which he was paid fifteen pounds each. According to the ever handy BoE inflation calculator that is the equivalent of £1651.03 per, or £21463.39 for the lot, $33,053 in today's reserve currency for 15 days work. Not rich but not bad.

More on Churchill another time but here are a couple more factoids: He charged a half-crown (2 1/2 shillings, $11.38) per word in the 1930's, in 1936 his writing income was the equivalent of $800,000 now.

Again, not rich but able to afford his Pol Roger.

Then he went on to become the highest paid scribbler of his day and did some other stuff too.

From Priceonomics:

It's no secret that technology disrupted journalism’s business model, and it has yet to recover. What's puzzling is that the disruption seems to have created lots of losers but no new winners within journalism.

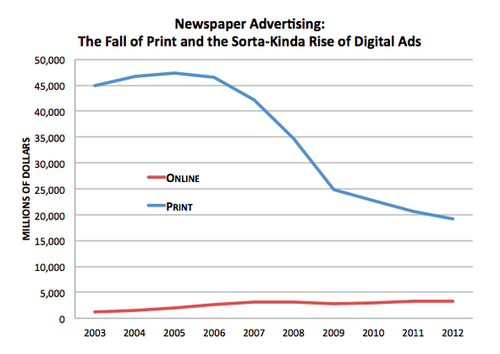

To quickly recap, the first blow was online alternatives like CraigsList taking away newspapers’ classifieds business, which represented around 50% of big papers’ revenue. The next blow has been the inability of newspapers to replace print advertising money with digital advertising money as readers go online, as aptly demonstrated by this graph from The Atlantic:

The result is that employment numbers for newspapers look like this:

An editor at The Atlantic has declared that “So far, there isn't a single [business] model for our kind of magazine that appears to work.” Pew Research Center’s 2013 report State of the News Media is full of doom and gloom as it chronicles the industry’s decline.

Newspapers’ supporters fret that we could soon see an American city without its own newspaper. We sympathize with concerns about the very real impact the loss of a regular paper can have on a city. But from an economic perspective, we want to know why big market newspapers have failed to capitalize on smaller papers’ struggles.To understand why we would expect this, let’s look at how technology has changed the music industry. Online distribution has been as big a shock to its revenues as it has been for newspapers: file sharing and digital music contributed to the music industry’s revenues being cut in half from 2000 to 2010.

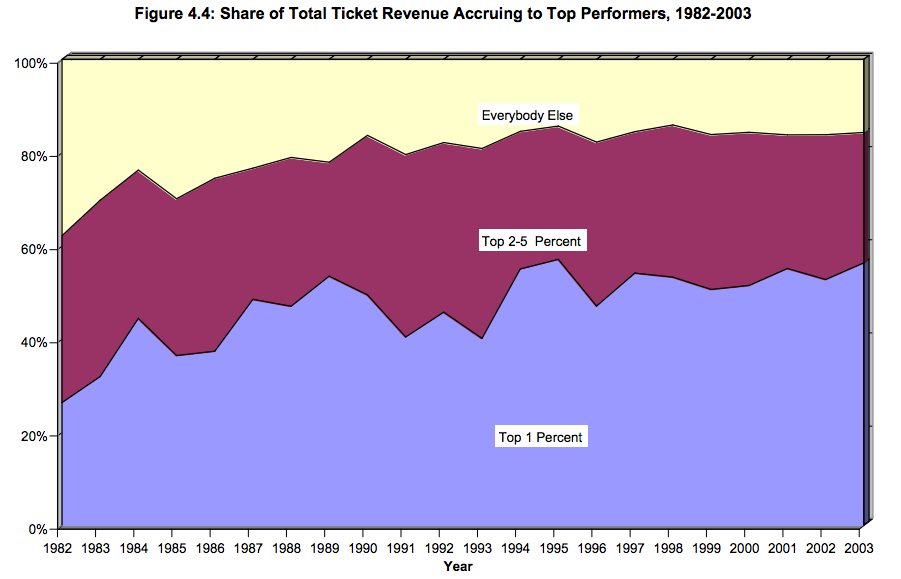

But at the same time, it has been part of a trend that has made musicians at the top of the hierarchy richer at the expense of the rank and file. In terms of concert revenue, for example, the top 1% of earners - big name artists like Justin Timberlake and Rihanna - increased their share from 26% in 1982 to 56% in 2003.

A theory typically proposed to explain the concentration of profits is the “superstar effect,” advanced by economist Sherwin Rosen in 1981. It applies to industries such as music, where consumers can jointly enjoy a good. (If I buy a Beatles CD, I do not keep you from enjoying The Beatles, just as we can both attend a Beatles concert.) In such industries, technology allows superstars to serve more of the market and profit more, although at the expense of smaller players who lose out on customers.

Writer Eduardo Porter explains the superstar effect in the music industry:News, like music, can be jointly consumed....MORE“The reasoning fits smoothly into the income dynamics of the music industry, which has been shaken by many technological disruptions since the 1980s. First, MTV put music on television. Then Napster took it to the Internet. Apple allowed fans to buy single songs and take them with them. Each of these breakthroughs allowed the very top acts to reach a larger fan base, and thus command a larger audience and a bigger share of concert revenue.”